Generation VIII: Ebenezer is "Obliged to Enter Another Wilderness"

The Puritan practice of generously increasing and multiplying eventually created population pressures in Dedham. By the middle to late 1700’s, according to an 1827 History of Dedham:

The people seem to have had a strong dislike to the introduction of new comers into the town. The reason of it is obvious, they might be expensive, and... they might occupy the places wanted for their sons, who might thereby be obliged to emigrate into another wilderness... From an inspection of the assessors’ books in 1736, I recognize the numerous descendants of some of the first settlers, with an extremely small number of new names. The Colburns, the Gays, the Ellises, the Farringtons, the Fishers, the Guilds, the Metcalfs, the Richards, and the Whitings, descendants of men of these names, had branched out into families from eight to fifteen in number, and did then constitute a considerable portion of the inhabitants... Ref

Title page of Erastus Worthington's 1827 History of Dedham.

Three generations after Nathaniel, a landless youngest son, left England to seek his fortune in the wilderness of Massachusetts, not all of his desendants could remain in Dedham. Joseph's youngest son Ebenezer was “oblighed to emigrate into another wilderness.”

Ebenezer moved twice. He and his wife first went to a newly established town about 50 miles to the west.

Princeton, Massachusetts

According to a 1915 history of the town of Princeton:On October, 1759, certain tracts of land… comprising about 15,000 acres, were, by Act of the General Court, made a District, to which the name of Prince Town was given… at the time this Act was passed the storm and stress period of the early settlement of New England had passed. The fierce conflicts with the aborigines had ended in the triumph of the white man… The territory now included within the boundaries of this town was one of the few tracts in the State which was unoccupied at this time. Ref

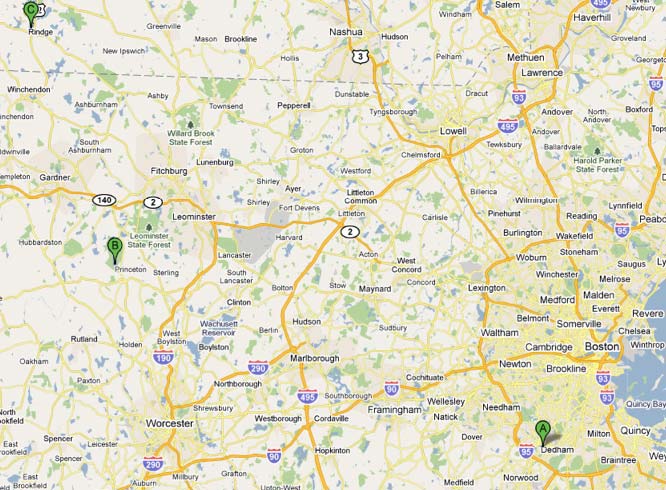

Portions of southern New Hampshire and eastern Massachusetts.

A: Dedham, MA B: Princeton, MA C: Rindge, NH.

For a long time, title to this land had no practical value to colonists anyway, because a series of wars made settlement too dangerous:

- 1702-1713 Queen Anne’s War

- 1722-1725 Dummer’s War. During this one, natives killed and kidnapped early settlers of nearby Rutland, forcing evacuation of neighboring settlements.

- 1744-1748 King George’s War

- 1754-1763 French and Indian War

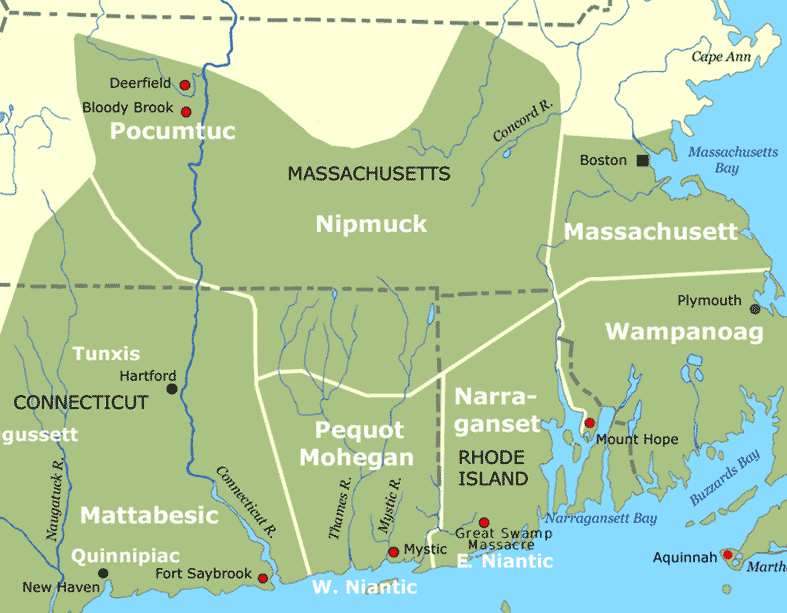

Approximate territories of southern New England tribes about 1600. The Nipmuck and closely related tribes controlled much of what is now central Massachusetts Ref

Some of these wars grew directly out of conflict with Native Americans unhappy with what had happened to their land and way of life. Others were colonial sideshows to wars between European powers. All made life risky for a colonist on the frontier, which still included central Massachusetts.

By 1759, the colonists had defeated and suppressed the Nipmuck. Eastern towns sold their claims to a consortium of “land jobbers.” These speculators subdivided, traded, and in time either sold or rented the land to families who actually wanted to live in what became Princeton.

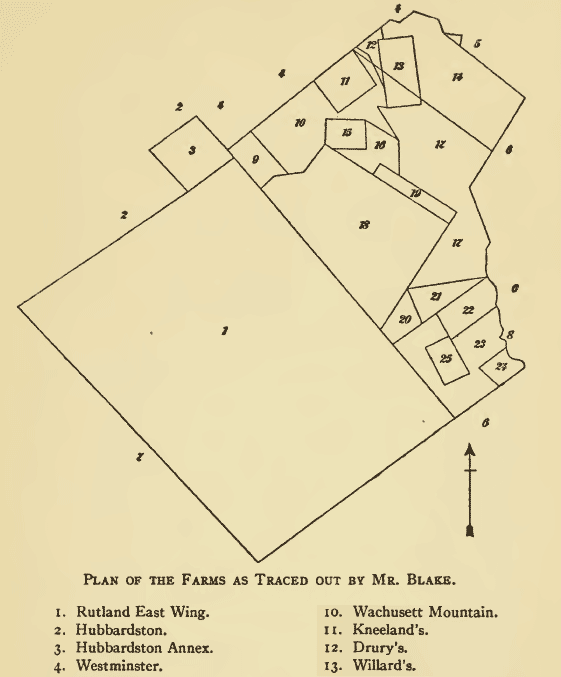

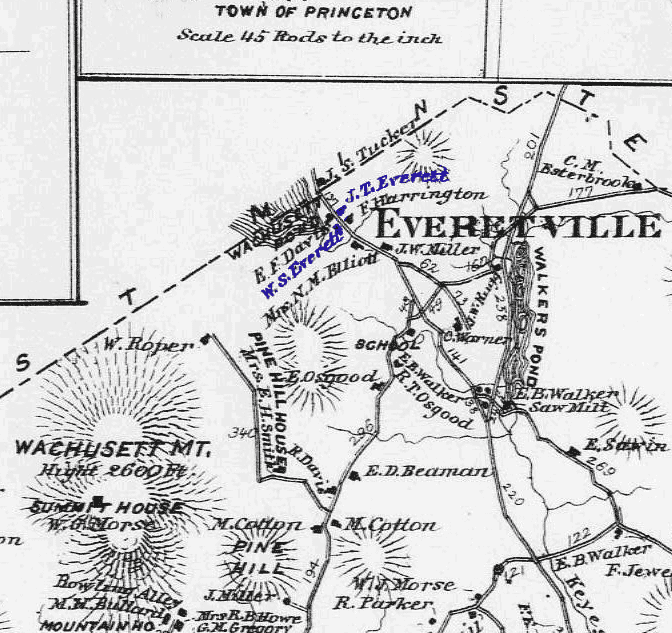

Map of subdivisions of Princeton at the town’s founding in 1759. Colburn and Everett farms were in tract #11, at the north, abutting Westminster and just north of Mount Wachusett (#10.) Ref

The Colburns seem to have purchased part of David Everett's farm. In a story about David's son in the Princeton history, they are likely the "old neighbors from Dedham" mentioned:

The father came from Dedham and within a year of his marriage purchased a hundred acres or more, adjoining land already owned by his wife's father. It was in Lot No. eleven (11) on the west side of Wachusett Mountain, on the old county road to Barre. On this land he erected two or three dwelling houses and a blacksmith shop, all of which he sold not long afterward, the larger part to some of his old neighbors from Dedham. The locality of the house is known, and is nearly opposite the schoolhouse now designated as No. 8. Ref

The widow kept the family together, though doubtless with difficulty, as her husband left no real estate, and but little personal property, while all the money, as far as is known, that the widow received as pay for his military service was sixteen pounds. RefWhen the Colburns moved on to New Hampshire, they seem to have been bought out by another Everett, cousin Joshua. In 1781 Joshua also bought a neighboring property, the confiscated homestead of a “loyalist absentee.” Joshua Everett named a village after himself which still appeared on maps a hundred years later, but no longer does so today.

The Colburn and Everett families apparently kept in touch. Twenty years later David's widow Susanna married a man from New Ipswich, NH, next door to the town to which the Colburns moved.

An 1870 map of northern Princeton shows two Everetts living in “Everetville,” on opposite sides of a road running along Wachusett Lake.

Ebenezer in the Revolution

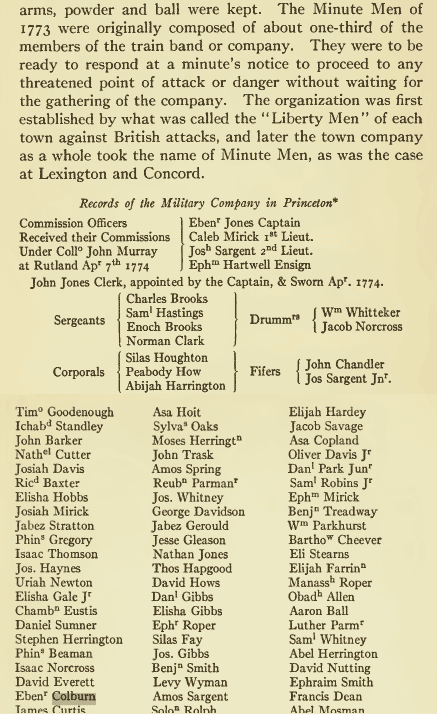

Excerpt from pages of the Princeton town history describing the activities of Princeton's "Liberty Men" and "Minute Men."

The minutemen of 1773 were originally composed of about one-third of the members of the train band or company. They were to be ready to respond at a minute's notice to proceed to any threatened point of attack or danger without waiting for the gathering of the company. The organization was first established by what was called the "Liberty Men" of each town against British attacks, and later the town company as a whole took the name of Minute Men..."Though Princeton may indeed have used the term loosely, "minuteman" is usually reserved for the ready-response team, required to be under 30 years of age. Ebenezer was 36 in 1774, the busy father of six living children.

Minuteman officers could be older. Back in Dedham, Nathaniel's older brother Jonathan was a lieutenant in Captain David Fairbank’s company of minutemen. That company marched in response to the famous alarm of Paul Revere on April 19, 1775 and fought in the Battle of Lexington. Ref Jonathan went on to other military service in the Revolution; the musket he used is still owned by a descendant.

Whatever his military status, Ebenezer and his wife Mercy took part in extraordinary events. At a town meeting on the 14th of June 1775, “a motion was made to see if the town would support independence, if it should be declared; and it was voted unanimously to concur.”

On the memorable 19th of April, 1775, the arrival of a messenger shouting, ‘to arms! To arms! The war has begun!” and the ringing of the church bell summoned the people together. In a short time the minute-men were paraded on the common and took up their line of march towards Lexington and Concord. Ref

Coincidentally, another Ebenezer Colburn of military age lived in a town next door to Princeton. He was a descendant not of emigrant Nathaniel but of the other prolific emigrant Colburn, Edward. (As if the two families conspired to confuse genealogists, his father was named Nathaniel.) This Ebenezer became First Lieutenant in the First Leominster company of Colonel Abigah Stearn’s Eighth Worcester Regiment on March 24, 1776.

In a list of soldiers in a New Hampshire-based regiment of the Continental Army in 1776, an Ebenezer Colburn appears among the Privates. Ref

Genealogies of both Colburn families (and applications for D.A.R. membership) claim their Ebenezer as the private in Bedel’s regiment. (Some genealogies also erroneously list Princeton Ebenezer as a member of the Leominster militia.) Leominster Ebenezer was 46 in 1775, and also had young children. An 1897 History of Worcester County is quite detailed about the events of his life, but does not mention the Continental Army. Since he was made an officer in the Massachusetts militia in March 1776, it seems doubtful that three months later he would have somehow enlisted as a private in the Continental Army.

That either man would have enlisted in a New Hampshire regiment is unlikely. Although both towns are near the southern border of that state, most of Bedel’s Regiment came from the northern part of New Hampshire (perhaps the best place to recruit, if your plan is to invade Canada.) Princeton Ebenezer did later move to New Hampshire, a few years after the war, so he may already have had connections up north. A third Ebenezer Colburn of military age could have existed, though no other record of such a person survives. The simplest explanation is that Hammond’s 1885 list is in error, and neither Colburn served with Bedel in the Continental Army.

Redemption Rock

Upon the rock fifty feet west of this spot Mary Rowlandson wife of the first minister of Lancaster was redeemed from captivity under King Philip. The narrative of her experience is one of the classics of colonial literature.

Redemption Rock, where the return of Mary Rowlandson was negotiated in 1676. She later told the story in The Sovereignty and Goodness of God: Being a Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson.

Google Earth view of northern Princeton, MA in 2011. The roads in the 1870 atlas all still exist, but the area of the Colburn and Everett farms has mostly reverted to forest. Redemption Rock sits center top. At the bottom left, the north face of Mount Wachusett has been carved into ski trails.

North to New Hampshire

In 1779, eleven years after they moved to Princeton, Ebenezer and Mercy Colburn moved on to Rindge, NH.

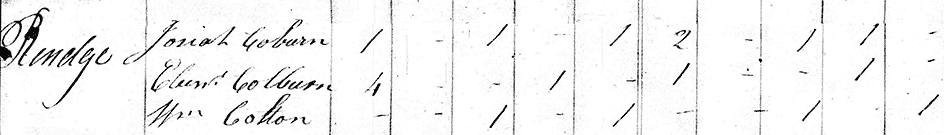

The Constitution of the United States, ratified in 1789, specified that an "Enumeration" of the population would take place every ten years. In the first census of 1790, Ebenezer appears as head of household, living in Rindge with two “free white males under age 16 years" and two “free white females.”

Colburn family entry from the first United States census in 1790, shown below the categories from another version of the form. There are entries under "Free white Males of 16 years and upwards," "Free white Males under 16 years," and "Free white Females, but no entries under "All other free Persons" and "Slaves."

In the 1800 census, Free white Males and Free white Females are each given columns for five age brackets (under 10 10-16, 16-26, 26-44, and 45 and upwards.)

Living with Ebenezer and Mercy (each in the 45 and Upwards column) are one male under 10, one 16-26, and two females 20-44.W The male 16-26 is probably the youngest son, Isaac, born 1782.

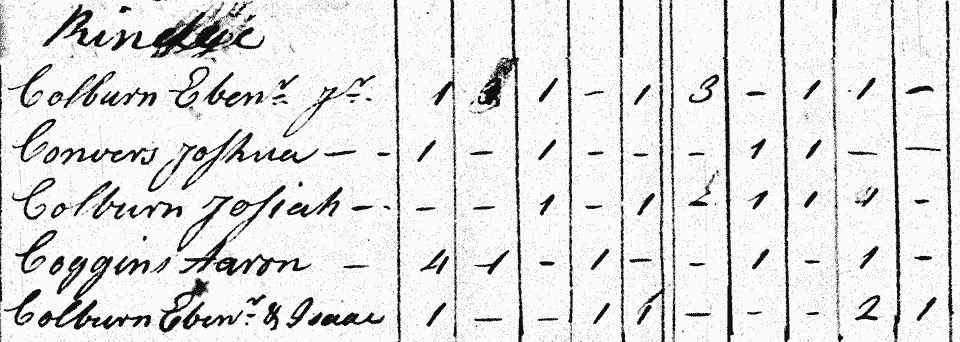

In the 1810 census, the same categories were used as those for the 1800 census.)

The 1810 census included separate entries for Ebenezer's eldest son (Eben’r Jr.) and "Colburn Eben’r & Isaac." (There is also an entry for Colburn, Josiah, of no known relation.) By the time youngest brother Isaac came of age, eldest brother Ebenezer Jr. had already established his own farm. He and wife Hannah went on to have fifteen children (even in a prodigiously fertile family, this was may have been the high point.)

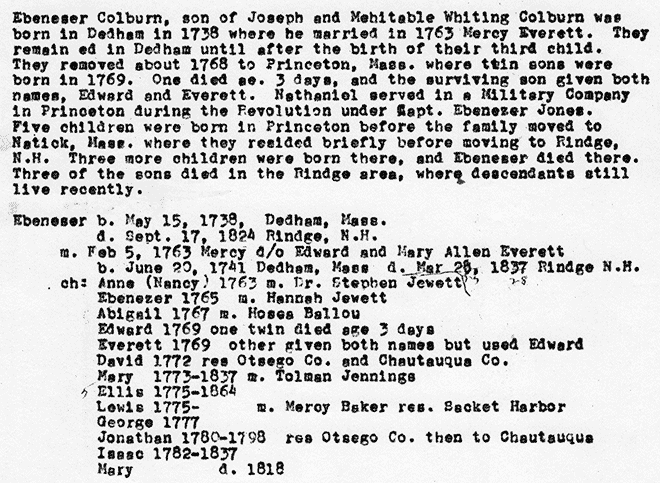

Ebenezer and Mercy (also listed sometimes as Mary) appear in the histories of both small towns in which they lived. The 1915 history of Princeton is more accurate and complete, including information about where many of the brothers who moved west lived out their lives. It omits youngest brother Isaac.

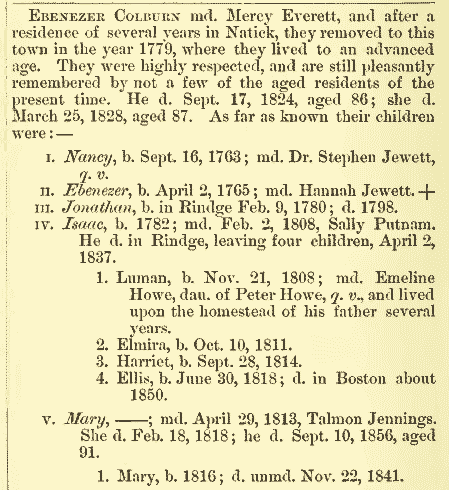

The Colburn family as remembered in the 1915 History of Princeton cited earlier. Ref

Isaac seems to have broken from the youngest-brother pattern and stayed on in Rindge, perhaps in part to take care of his parents, who by then were in their 70’s. A history of Rindge, published decades earlier than the Princeton history in 1875, states that his son Luman “lived upon the homestead of his father several years.” The homestead in question may in fact have been that of his grandfather.

The 1875 history confuses Princeton with Natick. It lists all the children who remained in New Hampshire but omits those who moved west, with the possible exception of son Jonathan. Both the Princeton and Rindge histories have him born in 1780 and dying, at the age of 18, in Rindge in 1798. Genealogies of the New York Colburns have him moving west with his brothers, marrying, fathering four children, serving in Cleveland's regiment of the New York Militia during the War of 1812, and dying in 1814 either of war injuries, typhus or typhoid.

The Colburn family as remembered in an 1875 History of the Town of Rindge. Ref

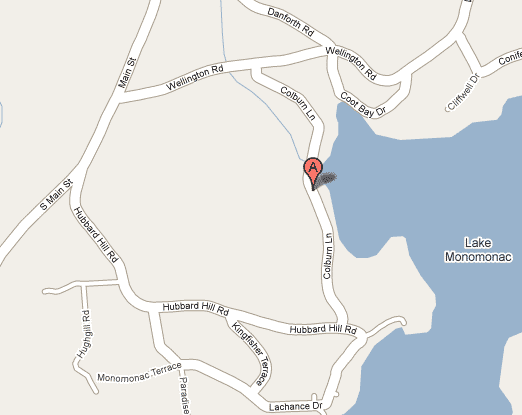

Colburn Lane

Colburn Lane runs along Lake Monomonac in Rindge, New Hampshire

Though it would be pleasant to imagine generations of Colburns enjoying a refreshing dip in the lake after a hard day farming, Monomonac is an artificial lake, created in 1923. The land Ebenezer farmed may well now be under water.

On to One More Wilderness: Upstate New York

Ebenezer and Mercy Colburn had eight sons that survived to adulthood. The eldest, Ebenezer Jr., and the youngest, Isaac, stayed in Rindge. The six middle sons all departed for the next frontier: central and western New York State, where the defeat of the Iroquois during the Revolution resulted in the opening up of new lands to farmers from New England. The background to this change will be told in the next chapter.

Eleanor Rider genealogy summary of the life of Ebenezer Colburn