Yet Another Wilderness: Upstate New York

Before following the specific story of the family members who lived through that period, we will examine the momentous changes that set the stage for their arrival.

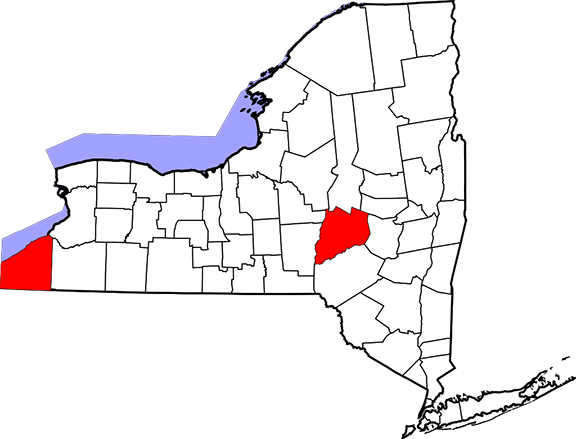

New York State

Left: Chautauqua County

Right: Otsego County

1780's-1790's: A Land Rush in Western New York

Displaced: The Land of the Iroquois

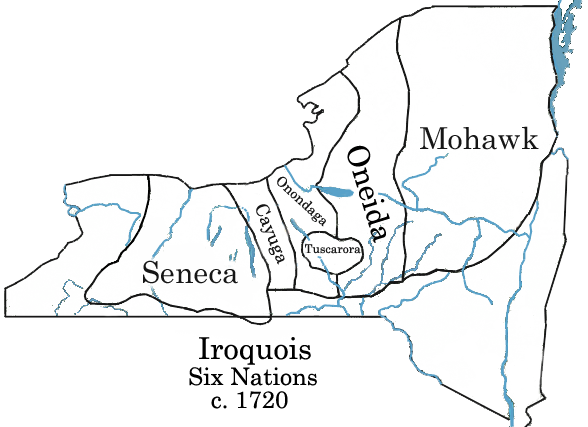

For centuries, most of what became upstate New York was the territory of five Native American tribes who spoke a common language, known to colonists as the Iroquois (they call themselves Haudenosaunee, “People of the Longhouse.”) Between 1000 and 1500 A.D. the Iroquois mostly lived in fortified villages. They abandoned this system in the 1600’s when European diseases that decimated Native populations across the continent struck hardest where people lived in concentrated villages. Ref

The survivors shifted to living along the rivers in smaller, decentralized villages that could be easily moved in times of war or epidemic. About the same time, the tribes formed the Iroquois Confederacy. This political and cultural union helped make the Iroquois dominant among Native tribes far beyond their upstate New York power base, and gave them a strong diplomatic position from which to negotiate with the French and English colonial powers. As English colonists displaced other tribes whose traditional lands lay along the coasts and major rivers, the Iroquois took in refugees from tribes from Virginia, Maryland and eastern New York, along with an entire closely-related tribe displaced from North Carolina (the Tuscarora).

French explorer Samuel de Champlain's sketch of his unsuccessful assault on a stockaded Onondaga village in 1615. The walls surround a group of longhouses.

Sometimes colonists made an effort to “extinguish Indian titlement” to the land where they built settlements, paying (or promising to pay) Natives for title to the land. Sometimes there was no such effort. Land-hungry colonists “squatted” on promising riverbank tracts, hoping that their “improvements” would make ownership a fait accompli. Native Americans did not fully understand or accept the European concept of “ownership” of land. Disagreements about who had which rights to what land frequently sparked acts of violence wherever Natives and colonists coexisted.

"Letters Patent" and the first Treaty of Fort Stanwix

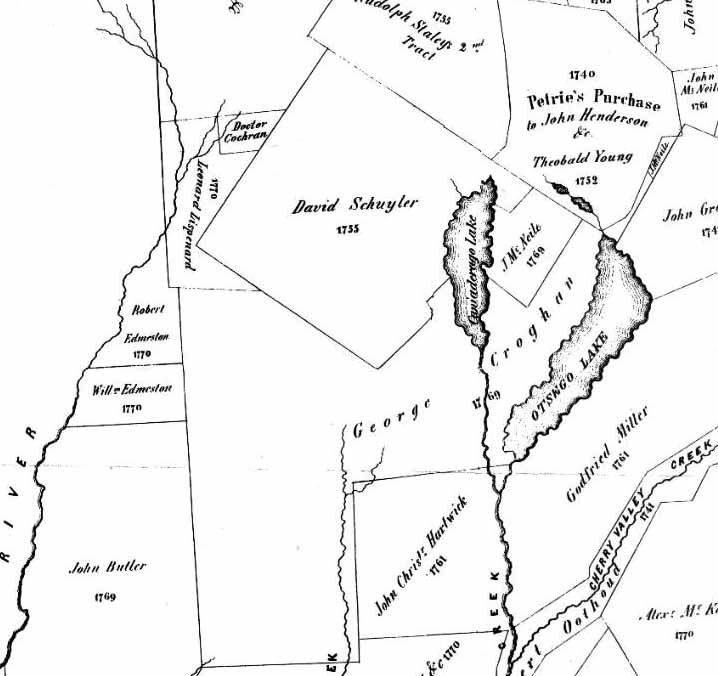

Schuyler’s Patent, in the northwest of what became Otsego County, comprised 43,000 acres, granted in 1755 to a group of 22 men from the highest levels of New York society, including members of the Schuyler, Livingston, Van Cortlandt and Stuyvesant families. Further west, two much smaller (5000-acre) patents were awarded to brothers named Edmeston who had served the British army during the French and Indian War.

Early patents in what became northern Otsego County.

Patents referenced in this history:

David Schuyler, center top square, granted 1755.

Leonard Lispenard, west of Scuyler's: granted 1770.

Edmeston brothers (Robert and William), center left, below Lispenard, granted 1770.

George Croghan, center below Schuyler's, granted 1769

From Map of the Head Waters of the Rivers Susquehanna & Delaware, Embracing the Early Patents on the South Side of the Mohawk River (Simon de Witt, 1790)

Deeds and maps today still make reference to the original patents and their subdivisions.

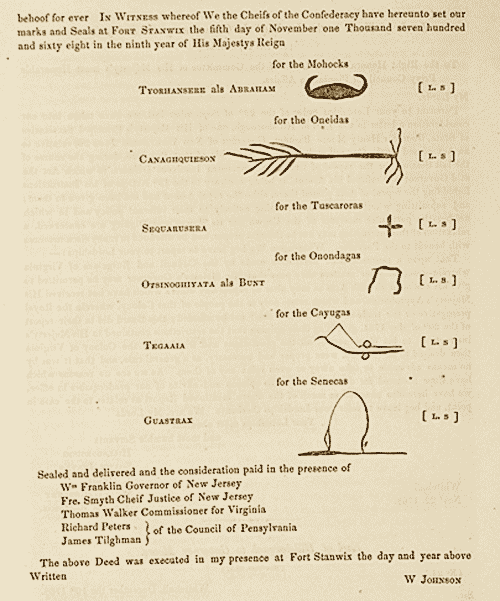

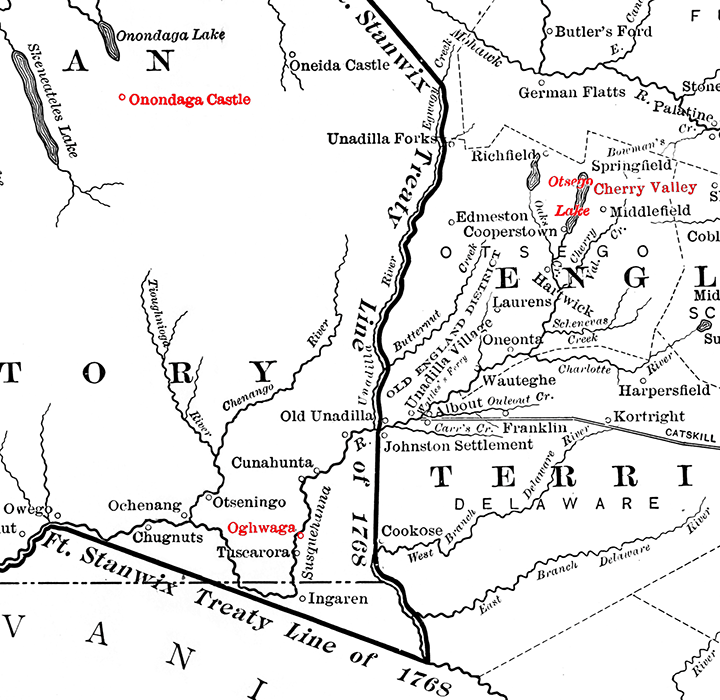

Sometimes patents were awarded after the Iroquois ceded title, and sometimes before. In 1768, representatives of the Iroquois and four British colonies met at Fort Stanwix, a British military base near the headwaters of the Mohawk (which later became the city of Rome, NY.) There they signed the first Treaty of Fort Stanwix, in which the Iroquois ceded title to all territory east of the Unadilla River (along the western edge of the map above.) The treaty supposedly also covered lands as far away as Kentucky that the Iroquois claimed through “right of conquest” of the Natives living there. The colonial authorities hoped that drawing clear boundaries would end frontier violence, while the Iroquois hoped it would limit British colonial expansion.

Transcript of the signature section of the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix Ref

In private meetings with leading Iroquois sachems, [Sir William] Johnson, [George] Croghan and their friends (including Gov. William Franklin of New Jersey) bought the Indian title to almost all the land acquired in New York, thereby cheating the Crown that they were supposed to serve. RefIn making these purchases, later certified by the colonial governor, most of the patentees put no money down. Sometimes this was because they had not the means.

Colonel George Croghan, an ambitious and charismatic Irish immigrant trader, won the largest patent in the Otsego area: a 100,000-acre tract that included Otsego Lake, as well as several smaller patents. Instead of cash, Croghan gave the Iroquois “promissory notes.” Most of Croghan's notes eventually proved worthless.

The American Revolution

Before George Croghan and other patentees could cash in by subdividing and selling off their newly acquired land, a conflict erupted that would completely change the rules of the game.

Many Americans think of the Revolutionary War as a relatively civilized affair, compared with brutal, devastating conflicts that came later. Textbooks write of red-coated British professional soldiers squaring off against scrappy colonial farmers-turned-soldier, with little if any mention of casualties among civilians.

In western New York, the Revolution was the scene of utterly devastating “total war," comparable perhaps to Sherman's march through Georgia nearly a century later but waged against a much more vulerable population.

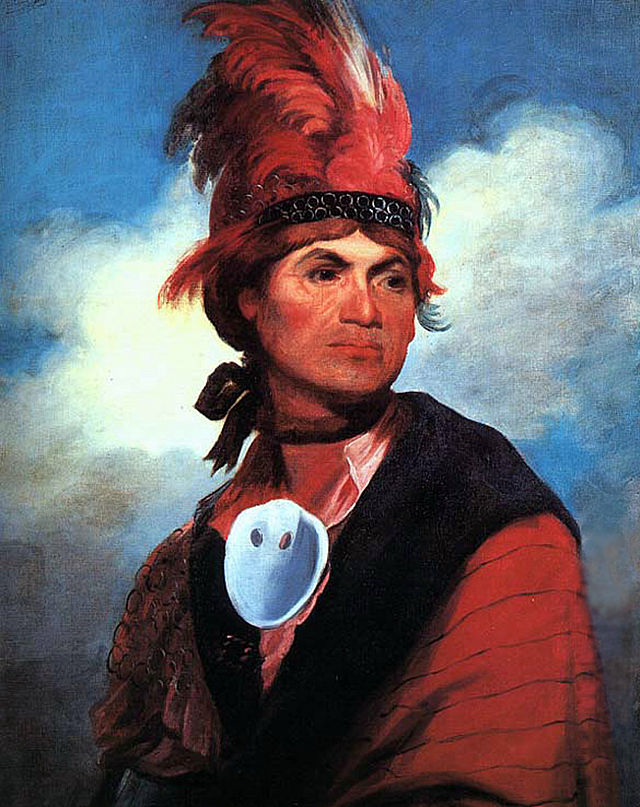

Raiders from both sides crisscrossed the area that eventually became Otsego County (at the time, part of a much-larger Tryon County.) Continental Army soldiers from Cherry Valley destroyed the farms of suspected Loyalists further west. Loyalists led by the Mohawk Joseph Brant, based in a large Iroquois town called Onoquaga, attacked settlements at German Flatts and Springfield. Those living in between had to abandon their homes, taking refuge either in Onoquaga or Cherry Valley, depending on their political sympathies.

In October 1778, Continental soldiers destroyed Onoquaga. A few weeks later the Loyalists and Iroquois struck back, attacking the village of Cherry Valley and its military garrison. For the duration of the war, Otsego was close to uninhabited. Ref

The following year, General George Washington ordered total war against the Iroquois.

Joseph Brant (1743-1807)

by Gilbert Stuart (1786)

George Washington, Terrorist?

Orders of George Washington to General John Sullivan, at Head-Quarters May 31, 1779:The Expedition you are appointed to command is to be directed against the hostile tribes of the Six Nations of Indians... The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements, and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible...

I would recommend, that some post in the center of the Indian Country, should be occupied with all expedition, with a sufficient quantity of provisions whence parties should be detached to lay waste all the settlements around, with instructions to do it in the most effectual manner, that the country may not be merely overrun, but destroyed...

After you have very thoroughly completed the destruction of their settlements; if the Indians should shew a disposition for peace, I would have you to encourage it... But you will not by any means listen to any overture of peace before the total ruinment of their settlements is effected. Our future security will be in their inability to injure us and in the terror with which the severity of the chastisement they receive will inspire them.Ref

George Washington at Princeton 1779

(Charles Willson Peale - U. S. Senate)

It is sobering to read “The Father of Our Country” giving explicit orders to "lay waste all settlements" so as induce "terror" in a population "of every age and sex."

Sullivan carried out Washington's orders faithfully, effecting the "total ruin of their settlements." The Iroquois gave Washington a less honorific name: Conotocaurious, translated variously as Burner of Towns, Devourer of Villages or He Destroys the Town. Washington was proud of this designation, and instructed emissaries to use it when negotiating with Natives to remind them of how dangerous an adversary he could be.

The Sullivan Expedition

Map showing the boundary between Indian and English territory (Ft. Stanwix Treaty Line) established in 1768, adapted from Francis W. Halsey, 1901.

The Continental Army destroyed Onoquaga (on the map, Oghwaga) in fall 1778. Loyalists and Iroquois allies attacked Cherry Valley a month later.

In 1779 the Continentals destroyed all but one of the Iroquois towns west of the treaty line.

The troops had little to do in what became Otsego County, where all they saw was ruined settlements and Iroquois cornfields flooded by the breaking of the dam. According to anthropologist Anthony F. C. Wallace:

Although Sullivan’s army did not inflict many military casualties, it succeeded in laying waste all the surviving Indian towns on the Susquehanna River and its tributaries, all the main Cayuga settlements, and most of the Seneca towns. RefBy the mid 1790’s the Iroquois population of western NY had been reduced to 30% of what it had been before the war. The 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the war between Britain and the new United States did not mention the Iroquois at all. Forced to negotiate from a weakened position, they soon lost most of their land.

Arrival of the Yankees

Patent-holders had varying ideas about how to develop their land. Some, such as John Tunnicliff, imagined carving grand manorial estates out of the wilderness. Owner of an estate in Derbyshire, before the Revolution he began building a grander version in Exeter, NY, only to see his efforts destroyed during the war. Others attempted to follow the English model of tenant farming, renting out parcels to the land-hungry poor and collecting rent either in money or crops.

The poor man… will generally undertake about one hundred acres. The best mode of dealing with him, is to grant him the fee simple by deed, and secure the purchase money by a mortgage on the land conveyed to him. He then feels himself… as a man upon record. His views extend themselves to his posterity, and he contemplates with pleasure their settlement on the estate he has created… RefAs a descendant of one Yankee farmer who "undertook about one hundred acres" in what became Otsego County in 1799, I look back on my five-times grandfather's investment with gratitude, and the sense that he would indeed contemplate with pleasure (albeit mixed with some consternation) what his heirs have wrought over the many generations that have passed since his time.

Cooper chose this approach partly out of democratic idealism, and partly because it offered the rapidest way to pay back the debts he had incurred during the process of gaining control of Croghan's patent. His timing was excellent, because thousands of tough, shrewd, thrifty Yankee farmers were hungry for just such an opportunity.

In the mid and late eighteenth century, population growth in the long-settled parts of New England sent Yankees in motion northward and westward in search of the freehold land that grew increasingly expensive at home…

By selling freeholds, Cooper energized the Yankee skills at clearing the forest and making new farms. Ref

William Cooper (1754-1809) by Gilbert Stuart.

After the war Yankee migrants flocked to upstate New York in numbers that overwhelmed the old stock inhabitants, the diverse medley of Dutch, German, Scotch, English, and Huguenot French collectively called Yorkers. Compared with the diverse Yorkers, the Yankees were a homogeneous people. Almost all had descended from seventeenth-century Puritans who had fled from England to colonize Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and southern New Hampshire.Since they were accustomed to it, Yankees would accept hilly plots the valley-dwelling Yorkers spurned. It also helped that during the 1780s and 90s the price of wheat surged in Europe, making it possible to turn a profit even in hilly Otsego, with its relatively short growing season.

A demanding region of long winters, stony hills, thin topsoil, and heavy forests, New England reinforced the Puritan impulses to frugality, industry, ingenuity, enterprise, and covetousness. In turn, those characteristics enabled the New Englanders to derive sustenance--sometimes prosperity, but rarely wealth--from the grudging land. Ref

Among the Yankees moving west from New England with their wives were six brothers named Colburn.